A collection of short stories is generally thought to be a horrendous clinker; an enforced courtesy for the elderly writer who wants to display the trophies of his youth, along with his trout flies.

Studies in Short Fiction,

Summer, 1994 by Francis J. Bosha

COPYRIGHT 1994 Studies in Short Fiction

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group

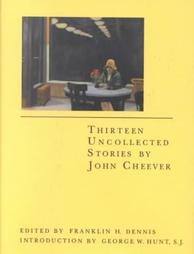

After several years of controversy and litigation with the Cheever Estate over the publishing rights to dozens of John Cheever's short stories, Academy Chicago Publishers has finally brought out Thirteen Uncollected Stories. This volume is a far cry from the more ambitious collection Franklin Dennis envisioned in 1987, when he first approached Cheever's widow with his plan of editing nearly 70 of Cheever's uncollected stories, a number of which were by then in the public domain.

This relatively slim collection of Cheever's early fiction, which dates from 1931 to 1942 (plus one from 1949), begins with his second published story, "Fall River." This piece, which Dennis has rescued from the obscure and long defunct The Left: A Quarterly Review of Radical and Experimental Art, was published when its author was just 19 years old. "Fall River" and the next two stories in this volume, "Late Gathering" (1931) and Bock Beer and Bermuda Onions" (1932), are set in the New England of Cheever's youth. These stories, and the much longer "In Passing" (1936) - which is, incidentally, more politically suggestive of its era than later Cheever stories would ever be - reveal the influence that Hemingway's style had on this tyro writer who was yet to find his own voice. Consider the following passage from "In Passing":

I decided then to go to New York. There was nothing I could do there. I decided late one afternoon when I had gone swimming alone and when I was walking back from the lake. The water had been cold and the air was cold. It was a cold, gray day.

Certain other stories reflect the economic hardship of the Depression, and include the short but powerful The Autobiography of a Drummer,, (1935), a story of a traveling shoe salesman who, during his best years, had a lot of friends and a lot of women." Late in life he can still remember the hotels and the train timetables, and remarks that even the "train smoke smells sweet to me." But, as he approaches 60 he finds that "methods of business had changed, faster than I could change," and at age 62 he loses his job. The salesman, and others like him, Cheever writes, "have been forgotten like old telephone books and almanacs and gas lights. . ." This story, which anticipates The Death of a Salesman by 13 years, seems inspired, to some extent, by the fate of Cheever's own father, though Cheever would no doubt bristle, as he usually did, at any suggestion of his writing "crypto-autobiography."

Other stories, however, such as the four that were written for the highly popular Collier's magazine, are marred by the slickness of popular fiction written to sell. Of these, "His Young Wife" (1938), "Saratoga" (1938) and "The Man She Loved" (1940), are set at the Saratoga or Belmont race tracks that Cheever knew well from his visits to Yaddo, the nearby artists' colony. These Collier's stories are competent if fairly formulaic pieces about love found, lost but finally found again. More important, though, is that the influence of Hemingway, apparent in the earlier stories, has given way to that of Fitzgerald, especially in the latter's use of nostalgia.

The last story in this volume, "The Opportunity" (first published in Cosmopolitan in 1949), was written when Cheever was 37, had already published some 90 stories, and had even collected 30 of them into his first book, The Way Some People Live (1943). He had also ventured, albeit unsuccessfully, onto Broadway, where his "Town House" series of stories, staged by George S. Kaufman in 1948, closed after only 12 performances. Drawing on that experience Cheever wrote of a dreamy 16-year-old girl who, by a remarkable chance, is offered the starring role in a new Broadway play. However, the girl rejects what to her widowed, impoverished mother is the opportunity of a lifetime, because only she can see that the play stinks." Her assessment is validated when the play closes in Philadelphia after just five performances. Credibility aside, the story of a naif with the innate sense to recoginize what the seasoned theatrical professionals cannot see is nonetheless engaging, and in no small way stands as Cheever's own wry view of Broadway.

These stories permit us to witness how Cheever's ability to turn a phrase, write convincing dialogue, and create complex characters steadily evolved from imitation and reliance on type. Cheever himself was well aware, as he wrote in 1978, that a selection on "one's early work will be a naked history of one's struggle to receive an education in economics and love." For that reason, one would have hoped that Dennis could have presented a more complete collection that included some of Cheever's pieces from the New Yorker, the magazine with which he was most widely identified from his first appearance there in 1935. Apparently, the terms of the settlement of the lawsuits made such an inclusion impossible.

In his introduction to The Letters of John Cheever, Benjamin Cheever wrote, by way of explaining why he was including some early examples of his father's "weaker correspondence": "I find it fascinating to watch him learning how to write." Readers of Thirteen Uncollected Stories can now say as much about these early short stories, written by one who would become a master of the genre.

3 comentarios:

¿Qué trece historias eran?!

¿Qué trece historias eran?!

He ampliado la información en el post con una reseña

Publicar un comentario